True Crime

Season 8 Episode 3 | 26m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Discover how the True Crime genre was shaped by its deep historic legacy in Los Angeles.

Host Nathan Masters examines old crimes like a 1950s Burbank murder and how these moments shaped the true crime genre. Featuring author Michael Connelly, former prosecutor Marcia Clark, podcaster Kate Winkler Dawson and historian William Deverell, the episode explores how Los Angeles' crimes have influenced storytellers and the city’s cultural identity.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

True Crime

Season 8 Episode 3 | 26m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Host Nathan Masters examines old crimes like a 1950s Burbank murder and how these moments shaped the true crime genre. Featuring author Michael Connelly, former prosecutor Marcia Clark, podcaster Kate Winkler Dawson and historian William Deverell, the episode explores how Los Angeles' crimes have influenced storytellers and the city’s cultural identity.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Lost LA

Lost LA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNathan Masters: This is a town where the palm trees throw long shadows, and the shadows don't always keep their secrets.

In Los Angeles, crime isn't just news-- it's the city's favorite fix.

From pulp magazines to the streaming charts, true crime and crime fiction have drunk from the same dark well, twisting facts into legend and legends back into fact.

But in this episode, we're chasing down the storytellers who still believe the truth matters, even when it leaves scars that never heal.

♪ ♪ For nearly a century, USC's Edward L. Doheny Jr.

Memorial Library has stood as a citadel of scholarship, but it's also a monument to a murder victim, an oil heir whose mysterious death in 1929 still haunts the city's memory.

I met with historian Bill Deverill, one of the foremost chroniclers of L.A.

's past, to unravel the enduring mystery of Edward L.

"Ned" Doheny's death.

This is one of the most sensational crimes in L.A.

history.

It's inspired wild speculation, conspiracy theorizing.

To this day, take a very, very wealthy scion of an oil tycoon's family, find him and his aide dead in the family mansion with gunshot wounds-- Nathan: Mm-hmm.

...it's going to spawn all kinds of conspiracy theories.

Nathan: Raymond Chandler fictionalizes this story, and he provides a fictional solution to the crime.

Yeah, there's any number of ways people have taken this.

Nathan: Yeah.

Perhaps the two men were lovers, and there was a lover's spat or a breakup, and that caused the death.

Perhaps Ned Doheny killed Plunkett, then killed himself, and the gun was put in Plunkett's hand.

Perhaps this was some kind of mob hit based on his father's activities in the Teapot Dome scandal.

Nathan: Right.

The actual resolution of this with certainty is likely to slip through our grasp.

Unless he could talk.

Nathan: In 1931, Ned Doheny's family gathered on the campus of his alma mater to break ground on a stately Romanesque revival library.

Financed entirely by oil tycoon Edward L. Doheny Sr., it opened its doors 15 months later as a limestone and marble memorial to his murdered son.

Few libraries can trace their origins to a notorious crime, but Doheny Library was born from tragedy, making it a fitting home for one of L.A.

's most important true-crime archives.

As the long-time Los Angeles correspondent for True Detective magazine, Edward S. Sullivan documented L.A.

's most lurid headlines, crafting stories about gangsters, grifters, and cold-blooded killers.

And it was Bill Deverill who championed bringing Sullivan's papers to the USC libraries, recognizing their value not merely as crime reporting, but as a window into the fears, fascinations, and moral judgments of mid-century Los Angeles.

The Ned Doheny murder is hardly the only case of L.A.

true crime that continues to fascinate and inspire speculation and conspiracy theories.

I mean, we're talking about the Black Dahlia murder, of course.

There's the Charles Manson murders.

There's the OJ Simpson case.

I mean, this is a genre that goes deep into L.A.

's history and culture-- 20th century, 19th century, 18th century, and on back from there.

And in Los Angeles, around the mid-20th century, you had a writer named Edward Sullivan, who was working here writing stories for this magazine, which was a huge circulation magazine, True Detective.

Yeah, there's a post-war phenomenon across America where suburbanites and metropolitan denizens are buying magazines, and the True Detective, true-crime genre is an important piece of that, and Sullivan's right in the middle of it.

I'm curious what caught your eye.

Why was this worth preserving in a university library?

This can be revelatory about the culture.

You can find things out about this.

There's remarkable photography in here.

There's the kind of narrative of crime and mystery and intrigue.

So, it's one avenue into a particularly important feature of Los Angeles.

What's in here?

Well, Sullivan was a writer.

He was not in law enforcement, although he fancied himself a detective.

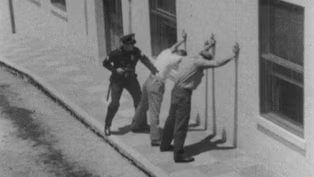

He had very good ties to the LAPD in the period.

And the archive shows that.

There are pictures of him with detectives who are-- in our era today-- utterly violating police protocol and privacies by saying, "Here, take a look at this."

Nathan: Here's a police mugshot.

The caption here, "(delete police numbers)."

And this, I believe-- this is the man himself.

This is so good.

Bill: Yeah, it looks like he's from Central Casting.

Nathan, laughing: Yes.

It looks like a noir actor, complete with fedora and an Inspector Clouseau mustache, a little bit.

But he's with LAPD detectives, and they're sharing information, clearly.

Nathan: Right.

I was reading about the Black Dahlia murder.

They actually used this magazine, True Detective magazine.

They planted a story in here, knowing that it would get the attention of a suspect.

It actually worked.

The suspect read about it, contacted this police psychologist.

The True Detective was, in some ways, a law enforcement tool.

In some ways, and it just shows you the hunger that people have, buying these magazines by the tens of thousands each edition.

You do get the sense if you read a lot of these-- and they date from the mid-'50s through the mid-'60s or thereabouts-- the turmoil in L.A.

It's growing so fast, and there are people from all over the world trying to make a go of it.

There's a lot of stress and tension in the culture, and in the worst aspects of human behavior, that erupts with this kind of stuff.

What can we learn about Los Angeles by studying true crime?

People have been finding all kinds of ways to do dastardly things to one another across time and across space and geography.

But in L.A., you've got a lot of ingredients that lead to this kind of record.

You have explosive metropolitan growth.

You have the implicit or sometimes explicit promise of fame and glamour and fortune.

You certainly-- culturally and physically-- you have a lot of sunshine, but that creates a lot of shadow.

And so, you have the light and dark of human experience.

And then you have plenty of people trying to make a living out here as creatives with pens in their hands and typewriters at the ready.

So, it's a kind of alchemy that can produce this result.

Nathan: As Bill explained, L.A.

doesn't just harbor criminals, it breeds crime storytellers.

And in 1953, one case gave them everything they craved.

On the evening of March 9th, wealthy widow Mabel Monahan was discovered dead in her Burbank home, victim of an apparent home invasion robbery gone sideways.

Police arrested three suspects, including 29-year-old Barbara Graham, accused of savagely beating the victim while her accomplices searched for rumored mob money.

The case had it all-- drama, violence, and a so-called femme fatale dubbed Bloody Babs.

Graham's trial became a media circus with reporters eager to play judge, jury, and executioner.

Seventy years later, it still raises urgent questions, not just about guilt and innocence, but about how we tell crime stories in the first place.

To explore these questions, I met with Marcia Clark, the former L.A.

County prosecutor who rose to prominence during the O.J.

Simpson trial.

Marcia's career has evolved beyond the courtroom.

She's now a best-selling author whose latest book revisits the Graham case.

We met on a soundstage inside a courtroom set, an uncanny echo of the real trial that once gripped the nation.

So, it's always fun to be on a set like this, right?

Marcia: Yeah, it is.

"The Fix," your show, was actually shot here, on this stage.

Yeah, we actually did an episode here.

So, it was really funny when I showed up, and I go, "Oh, my goodness, I remember this."

Nathan: Yeah, yeah.

So, your book is an entry in the true-crime genre.

But one of the subjects is also true-crime journalism... Yeah.

...in mid-20th century itself.

And, boy, do you have some biting criticism for that.

Marcia: I do.

We have all of this fake news stuff going on in today's world, and I really thought I'd look back into the '50s and find that it was better then.

It wasn't.

It was worse.

I mean, it was worse by far.

So, was part of it was the novelty that a woman was on trial and was facing the death penalty?

Yes.

So, that was a big deal.

You know, a woman accused of a heinous, violent crime.

That's something that we don't see every day.

Because women just don't.

On top of that, when the woman is also beautiful and doesn't look the part.

I don't think that that, though, was so much different back then than it is today.

Now, how does the way a trial is reported in the newspapers affect the proceedings in a courtroom like this, if at all?

Hmm.

You know, they're not supposed to affect anything that happens in the courtroom.

Nathan: In theory.

Marcia: In theory.

Nathan: Yeah.

We always tell jurors-- the judge instructs them-- "You must not watch, you must not listen, you must not read."

And they're very-- very good about telling them not to, but good luck.

Even in the '50s, they had these newsstands at every street corner that would display these bold-type headlines, and you could not walk past without seeing them.

And they were all over the place in front of the Hall of Justice, where her case was being tried.

So, I think it always does find its way into the courtroom.

If I go through the bibliography of your book, I see so many different newspapers cited.

And yet, there wasn't one dissenting opinion-- one reporter saying, "Hey, wait, this is not all going right."

Marcia: True.

While the trial was going on, everyone was reporting the same thing.

But there was one reporter, San Francisco Examiner reporter Ed Montgomery.

Instead of just reporting from a distant newsroom up in San Francisco, he decided to come to the courtroom.

Came and sat down for a few days and watched the proceedings and had his mind changed completely.

He watched her, he watched the two co-defendants, thugs, sitting next to her, and started analyzing the evidence against her and realized, "Something's wrong with this case."

And he changed his mind 180 degrees and wound up really contesting the narrative and saying, "I don't believe she's even guilty."

Now, when you talk about the way the reporters were studying Barbara Graham with their eyes and their pencils and making mountains out of molehills in terms of facial tics or a crack of a smile, for instance, you must have been feeling déjà vu a little bit.

Marcia: A little bit.

You know, and I didn't want to get into the Simpson case.

Nathan: Yeah.

But I also thought, look, if I don't draw this parallel, people are going to say, "Uh, hello..." Nathan, laughing: Right.

Marcia: You know?

Nathan: Right.

Today, we call it clickbait.

Back then, they called it "the scoop," but it's the same thing.

They're all looking for something new to say, and when they're covering on a day-by-day basis-- And they were doing it not only a day-by-day basis, but three times a day-- morning, afternoon, evening news.

It was crazy.

As close as they could get to a 24-hour news cycle.

And they were finding new things-- and they had to keep digging up new things to say.

So, the relationship between prosecutors and the press really has changed.

I mean, if you think about the Black Dahlia case, you had reporters and editors, like Agnes Underwood at the Herald-Express and Jimmy Richardson at the Examiner, they were in some cases two steps ahead of the police.

They would send the reporters down, and they would know what witnesses were gonna say before the police did.

Yeah, it was amazing.

There was a time when reporters really were investigators.

Nathan: Yeah.

Marcia: And it was cool, because they weren't constrained.

And in a way, it's very helpful to the police, because the police have to worry about the Fourth Amendment, right?

They can't just walk into a house... They can't just barrel through people's, you know, rooms and all that.

But a reporter can.

No state action.

It's a private citizen.

They can get sued for it, you know, trespass and whatever, but they come up with stuff.

And it's really kind of cool to read that.

So, your book is essentially reevaluating it, taking another look back at a very high-profile, heavily-reported true-crime case from the 1950s.

There have been attempts to do that with the O.J.

Simpson case, too, right?

The Ryan Murphy television series.

What can we learn by looking back at a case that was prosecuted, tried, decided, and reported long ago?

High-profile cases have a way of being impacted by what's happening in society at the time-- culturally, sociologically, politically.

People bring a lot of expectations, biases, thoughts, opinions to the case.

And so, when you can step back from whatever is swirling in the air at the time of that trial and look at it dispassionately, with the benefit of time, you can see things more clearly, I think, to teach us lessons about what went wrong and what went right.

How do we remember that lesson in future cases?

Nathan: As we moved from one courtroom set to another, trading dark wood for blonde, we couldn't help but admire how elegant it all looked.

Marcia let me in on a little secret-- real courtrooms are rarely this cinematic.

Whether they're old courtrooms or the new ones, I wish our courtrooms really looked like this.

So, Marcia, you also write fiction.

How can and how should true crime inform mystery fiction?

Well, true crime tells you how it really happens.

Nathan: Yeah.

So, you get the experience of how investigators work and how they do.

Michael Connelly has a team of detectives that he-- Well, I know one in particular that he works with all the time, because I worked with him as a DA.

Oh, wow.

Marcia: Yeah, Rick Jackson.

And Rick is wonderful.

He's not just a fictional character, he's a real character, and he's a fabulous guy, and he was a terrific detective.

There's nothing like having somebody who really did the job sitting next to you and saying, "Well, we would do this next," and, "We would do that next."

And I think it's also true when you're writing novels-- you know, in terms of legal novels, you know, legal mysteries and that sort of thing, to know how a case really does get put together and how it goes to trial, and what a lawyer really does.

And that's why knowing true crime, working in true crime really helps with novels as well, and people can feel when it's authentic.

They can tell when you've really done the job.

♪ Nathan: One person who's really done the job is Michael Connelly.

Before becoming a best-selling author, Michael worked the crime beat of the Los Angeles Times, mastering how to chase leads, cultivate sources, and earn the trust of cynical detectives.

Today, he brings that journalistic precision to his fiction.

With 39 novels and several hit TV adaptations, including "Bosch" and "The Lincoln Lawyer," Michael has constructed a literary universe that feels as authentic as the city it portrays.

So, there's true crime.

There's also crime fiction.

And these are obviously distinct genres, but there's some relation there.

How does your background as a crime reporter for the L.A.

Times-- how does that inform your work as a writer, not just of detective novels, but also of television?

Michael: In every way and all the time.

If I had not worked a crime beat for a newspaper telling true stories, I wouldn't be doing what I'm doing now, because it's kind of the foundation.

So, you wrote two mystery novels that were never published, before you moved to L.A.

Right.

And then you moved here, and the first book you wrote here was published.

Was there something about being in L.A.

that unlocked that for you?

I think it was.

I loved L.A.

from afar, and books and film, like "Long Goodbye," "Chinatown" are my favorite movies.

And when I saw "Long Goodbye," that led me to the books, Raymond Chandler's, and-- Nathan: Masterful books.

Yeah, and then there's Joseph Wambaugh and Ross MacDonald.

These were the people that made me want to become a writer.

All those guys have written-- wrote in different times, and I think, you know, the diversity of the city and its issues at the same time are really what I try to capture when I put that in a framework of-- usually a homicide investigation.

And I've gravitated towards cold-case unit, because these are time-travel cases.

They're very contemporary because of what they're doing now, but the case takes them back in history.

Your first book was-- if I remember correctly-- it was based on or inspired by a true-- an actual true crime.

Yeah, I mean, it's funny.

I came out here in 1987.

I was 30 years old.

I had tried to write two novels where I grew up in Florida.

And I was missing something, so I decided to change my life.

And I moved all the way across the country and took a job here in L.A.

And on the very first day I arrived, there was this big heist, where guys in the ATC-- three-wheeled motorcycles, went through the tunnels underneath L.A.

and then drilled up into a bank and took everything.

And it was never solved, to this day.

And, immediately, I thought, "This could be something I could try with my third novel."

And I was able to get my way into a briefing where detectives were telling other detectives how they did it.

And so, I got all the details, and that became the basis of my first published novel.

So, you started working on your first published novel at the same time you started working for the L.A.

Times.

Yeah, yeah.

Nathan: Wow.

So, these two careers are really intertwined.

Oh, yeah, I mean, I wanted to write crime fiction first, and with some advice from my parents, I went into journalism.

To me, my days as a reporter, they added up to 14 years, but still, they were days of research.

So, there's journalism embedded in your fiction?

I think so.

I mean, I hope so.

I had a press card that gave me access when I first started my career.

That was several years ago that I left being a working journalist, but I've kept access, and I use a lot of real people, and I gather stories all the time, true stories.

And then, if I have any kind of skill, I think it's determining what those stories mean or what their thing is.

Is it an anecdote?

Is it a chapter?

Is it a whole book?

But, usually, there's something-- there's truisms that are the starting point for all my made-up books.

So, one of the remarkable things about your work is it doesn't traffic in all these cliches about L.A.

I mean, I imagine that some readers, they'll pick up your books for the first time, they'll look in the back, and they'll see, "Oh, it's about a Hollywood homicide detective."

And they might think it's about something else, but then when they open up the book, they see the real L.A.

There's so many things going on.

There's so many things to choose from.

Why go down that road of the Hollywood tropes?

So, how do you choose locations for your book?

Well, I'm always looking for a new location.

You know, I'm never going to run out of places to write about in this city, but I'm always looking for something unique, something where-- I haven't hit before.

I had a guy fall off the roof of that building in one of the books.

Nathan: Right here?

Michael: Yeah, in my latest book, I, for the first time ever, go to Angelino Heights.

All my books, at some point, are in L.A.

Nathan: Yeah.

So, everywhere you drive in L.A., there have to be-- there are fictional murders or fictional cases that... I mean, there's a Michael Connelly landscape here.

It was interesting.

I thought this was public transportation, so I didn't check with anybody, and I wrote a book called Angels Flight where there's a double murder on there, and-- the book comes out, and I'm signing books, and somebody puts down a business card in front of me, and it says "Executive Director of Angels Flight."

And it turns out this is-- even though it's over 100 years old, it's always been kind of operated by private operators.

So, I guess, technically, I should have asked for permission to kill somebody on there, but they thought it increased ridership, so I skated on that.

I remember when I first watched the "Bosch" pilot-- that was now 10 years ago, right-- one of the things that struck me is that-- I think they were coming this way, they got on the train, and then when they got off, they were still-- they were in the right place, right?

You have a lot of geographic integrity to your stories.

I love that you say that.

That's a great phrase, "geographic integrity."

That was something-- not just me, but I insisted that we do that.

So, in the opening sequence, we go from a hillside in Echo Park, and Harry and Jerry are following someone, and it's a realistic path down this-- onto the metro and over to Mariachi Square, and it was a realistic follow, and you never see that.

It's like people jump in a car and-- at the police headquarters, and then they show up at Santa Monica Pier, you know, a minute later.

I think this is a place of endless fascination around the world.

I mean, I grew up on the other side of the country, and I was fascinated with this place.

Nathan: In some ways, it's the most documented but least understood city in the world.

Michael: Yeah.

Nathan: Maybe that inscrutability explains why Los Angeles has long been fertile ground for crime storytelling.

In the 1930s, the LAPD stepped behind the microphone to produce "Calling All Cars," a radio drama hosted by Chief James "Two-Gun" Davis and based on actual police cases.

♪ Radio announcer: "Calling All Cars," the copyrighted program created by the Rio Grande Oil Company.

Nathan: It was an early attempt to shape public perception, one that worked.

By the late 1940s, Jack Webb's "Dragnet" refined the formula, with more than 300 episodes brought to listeners nationwide, all with the department's full cooperation.

George Fenneman: The story you are about to hear is true.

Only the names have been changed to protect the innocent.

Nathan: Today, true crime has left the radio dial behind, but the genre didn't vanish.

It simply migrated online.

In 2014, Serial ignited a podcasting revolution, and the obsession shows no signs of waning.

One of the most thoughtful voices in that space is Kate Winkler Dawson, an author, journalism professor, and podcast host who brings historical perspective to the way we tell and consume true-crime stories.

I spoke with her remotely from a recording studio in Highland Park.

You've hosted or co-hosted-- is it now three true-crime podcasts?

Kate: Yes.

Nathan: And it seems like podcasts are now-- we consider that the default mode of true-crime storytelling.

And it probably goes back to the release of Serial.

I think Serial, absolutely.

Certainly with podcasting.

There's a long tradition of true-crime radio programs.

Have you listened to old radio true-crime shows?

A lot.

I patterned "Tenfold More Wicked" after those old shows, like the old CBS radio shows.

"Texas Rangers" was another one I've listened to.

So, we were talking about striking a balance between creating drama for the listener, but also a responsibility to the facts and to the truth.

And what's your sense of how these old radio programs struck that balance?

Kate: I would definitely say they're dramatized.

Nathan: Yeah.

The ones that are sort of the most egregious are where they're reinventing the dialogue that I know never happened, because everybody there is dead.

It is a way to tell the story.

It's not like a real source, where you're going to get real information.

What is it about this genre that fascinates you?

I love being able to find a crime story and figure out who the people are, figure out why I should care about that person, how do I frame their life, so that it makes you as a listener or the reader feel like these are not just characters that were made up for your entertainment.

And so, I think that the power of doing a crime story, a true-crime story, really is looking for the reasons why these things happen.

What are your responsibilities?

I suppose you have responsibilities as a journalist to the facts, but you also have some sense of responsibility to the victims of these crimes.

You do.

And, you know, I don't enjoy reporting on contemporary crimes, on current crimes.

So, I'm never gonna do something on the Menendez brothers or JonBenét Ramsey or Laci Peterson or any of the cases that we see kind of repeated over and over again.

And part of that is that I am so alarmed by the way that I think that sometimes the family members are treated.

And I think that I prefer to tell stories from-- that are much, much, much older, in which I still try to talk to the family members, but they are four or five generations removed.

Now, telling a really good story from history, though, can also be quite a challenge.

Part of history is you're limited, and you know that.

It's like, you look at your historical documents, and that's it.

You're not making this stuff up.

You can't-- This is not fiction.

You have to be so careful, as you know, about extrapolating too much and about exaggerating things.

What I have learned about being a crime historian is that the reason people kill has not changed from now all the way back to the beginning of time.

It's the same basic emotions that people have.

So, I think it's so valuable to learn about these to-- these crime stories, to just see the way these patterns work.

Do you consider this an extension of your career as a journalist?

Kate: Oh, absolutely.

First and foremost, you know, I am a journalist, which means I'm uncomfortable with not understanding my sources, whether or not I believe people, doing thorough fact checking, double checking and making sure-- spellings, everything, you know, making sure that I have covered all my bases.

And, you know, part of-- a little part of me wishes that everybody had to have some sort of journalism background before they put out content.

And I only say that-- It probably makes me sound like a total jerk saying stuff like that, like, "Oh, you can't-- Why would you gatekeep?"

Because these are real people.

Because they're hurt.

People get hurt listening to these stories.

And so, you know, I think my background in journalism has really taught me, I hope, a little bit of humanity.

Nathan: I think there are few cities that have a stronger association with crime storytelling than Los Angeles.

When you think of Los Angeles in the context of crime, what do you think of?

Oh, I mean, L.A.

Nathan: Yeah.

You know, I think L.A.

is such a transitory city.

You know, you have people coming in and coming out.

It's easy to blend in into different areas.

And I-- you know, I feel like it attracts a lot of different kinds of people.

So, anytime you have a big city like that, that you're drawing people there who are young, who are inexperienced, who are oftentimes alone.

I mean, that is the prototype for the victim of many killers we've seen throughout history.

Nathan: In a town built on illusion, truth can be a slippery thing.

But for the best crime storytellers, the goal was never just thrills.

It was clarity, a way to shine a light, however dim, into the places most people don't want to look.

♪ Crime show narrator: This is the city, Los Angeles, California.

It's a good place to live.

We try to keep it that way.

It's a full-time job.

Every 60 seconds, a crime is committed in Los Angeles.

In the Los Angeles Police Department's Communications Center, the telephone rings every 20 seconds, 24 hours a day.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 5m 8s | Michael Connelly credits his LA crime reporting experience as the foundation of his fiction writing. (5m 8s)

Preview: S8 Ep3 | 30s | Discover how the True Crime genre was shaped by its deep historic legacy in Los Angeles. (30s)

True Detective Helps in the Black Dahlia Case

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep3 | 1m 29s | True Detective Magazine was used as a tool to help hunt down the Black Dahlia murderer. (1m 29s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal