Sci-Fi Origins

Season 8 Episode 2 | 26m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

Uncover the origins of the sci-fi genre and its unique connection to historic Los Angeles.

Boldly go into the heart of science fiction storytelling and discover its deep roots in Los Angeles. From UC Riverside’s vast sci-fi collection to author Octavia Butler’s Pasadena, host Nathan Masters explores how Southern California became a launchpad for stories that imagine new worlds—and reflect our own hopes and fears.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Sci-Fi Origins

Season 8 Episode 2 | 26m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

Boldly go into the heart of science fiction storytelling and discover its deep roots in Los Angeles. From UC Riverside’s vast sci-fi collection to author Octavia Butler’s Pasadena, host Nathan Masters explores how Southern California became a launchpad for stories that imagine new worlds—and reflect our own hopes and fears.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Lost LA

Lost LA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNathan Masters: With its searchlight skies and cultural contrasts, Los Angeles has long inspired visions of the future.

Time and again, the city has set the stage for both hopeful dreams and dark nightmares, but these stories aren't just about imagined tomorrows.

They're about the people who dared to dream them.

Through science fiction, writers and fans alike could explore brave, new worlds and build communities where they could finally belong.

♪ This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill philanthropy.

♪ ♪ Stroll through UC Riverside's campus, and you might feel like you've stepped into the future.

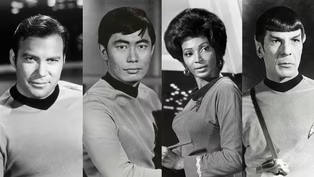

"Star Trek" creator Gene Roddenberry even filmed a television pilot here, but the university's sci-fi connection runs even deeper.

It's also home to the Eaton Collection of Science Fiction & Fantasy, one of the largest archives of speculative fiction in the world.

Man: Welcome, Nathan, to the Eaton Collection of Science Fiction & Fantasy here at UCR Library.

Masters: Here, I met up with science fiction librarian Phoenix Alexander.

Alexander: I'm particularly excited to show you these.

Masters: All right.

Alexander: So these are very scarce and very precious magazines of particular significance to science fiction, so this is "Amazing Stories."

Masters: 1926?

Alexander: 1926.

This is the first issue, so, as you can see, it's very delicate.

This was when science fiction really became consolidated as a genre.

Masters: Look at the authors here--H.G.

Wells, Jules Verne, Edgar Allan Poe.

Alexander: The table of contents is stacked and deliberately so by Hugo Gernsback, who was the editor.

In his editorial introduction, he lays out that this is a new sort of magazine, and he coins the term "scientifiction" of "scientific" and "fiction."

Masters: Uh-huh.

Alexander: He wanted to combine that sort of educational and adventure context.

Masters: I guess in me, this provokes the question, though, where did science fiction start?

Because, obviously, Jules Verne, H.G.

Wells were writing, and Edgar Allan Poe, we're talking about the 1800s.

Is there a generally agreed-upon progenitor of science fiction?

Alexander: This is a very big question.

It depends who you ask.

I would say the sort of standard answer would be 1818 and "Frankenstein," Mary Shelley.

Masters: Oh, Mary Shelley, yeah.

Alexander: Yes, and, again, that text was responding to scientific innovations of its day, right, particularly with electrical stimulation of muscles, and Mary Shelley was writing a very thrilling narrative around that, creating something really new in the genre.

As we get into the 19th century with the Industrial Revolution and technological innovations, and authors are really engaging with these developments and societal discoveries in new ways.

Masters: So this magazine was really that influential?

Alexander: Absolutely.

It actually started with our friend Hugo Gernsback, again, in 1934, where he founded the Science Fiction League, which was a club or a group that fans could join, although after a couple of years, it sort of declined, and then it was taken up by folks such as Forrest Ackerman to become LASFS, L-A-S-F-S, or the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

They would meet physically in locations in L.A.

like Clifton's Cafeteria and other places.

Folks could write in and become members, and that was really the first place on the West Coast that fans of the genre could meet and gather and discuss, you know, the latest stories, their own work, and so it was a hugely important group.

Masters: And you have materials relating to them.

Alexander: We have many archival materials related to them, including a fanzine collection.

Masters: Let's take a look.

Alexander: All right.

I will show you these.

Masters: Maybe some of these people started out as fans, but some of them became some of the best-known sci-fi authors.

Alexander: Yes.

Masters: Remember, like, Ray Bradbury, for instance, was affiliated with this group.

Alexander: That's right, and they got their start, many of them, Bradbury included, in fanzines.

Fanzines are not mass-produced.

They were printed by hand and circulated by fans... Masters: Wow.

Alexander: and so what we're looking at here is not quite the first, but the second issue of "Shangri L'Affaires," which was LASFS', Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society's, first publication, and this is from 1940.

Masters: And this is what you'd call a 'zine... Alexander: Correct.

Masters: which is short for "magazine."

Alexander: That's correct, so they would often feature illustrations, artwork, letters.

People would write reviews of things they'd liked or, certainly, didn't like.

It was really a way for the community to catch up with what happened at, say, conventions or gatherings that they might have missed.

These acted as kind of minutes of what was discussed so folks could still feel involved and feel active in the community through publications like this.

Masters: Wow.

Alexander: Many famous authors got their start in fanzines... Masters: Yeah.

Alexander: and Ray Bradbury was one of them, so, for instance, this one, "Imagination," which was a very early fanzine from '38, Volume 1, Number 9, is signed by Bradbury.

Masters: Wow, so this was before Bradbury was certainly a household name, but it was before he was really even known very well within national sci-fi circles.

Alexander: You know, in the thirties, he was contributing to 'zines like this.

Masters: He was a fan.

Alexander: He was a fan.

Of course.

Masters: That's what he was, yeah, first and foremost.

Alexander: Truly was.

I mean, even this table of contents, you have Ray Bradbury writing a piece on how to become a sci-fic fan... Masters: Yeah, Page 12.

Alexander: and this is Page 12.

Masters: "When paying your fare on the bus always drop in a Science Fiction League Official Pin by mistake," so this is the way to proselytize for science fiction.

Alexander: Yes.

That's right, and you can see that sort of grassroots, almost, organizing campaign is carried forward into something like the Save "Star Trek" campaign, so this is a letter from Harlan Ellison, who was a member of the science fiction community, and it's from the Save "Star Trek" campaign dated 1966, so really, you know, when the first season was airing.

Masters: And this is on the letterhead of the committee?

Alexander: I believe this was an impromptu committee formed to sort of save "Star Trek," and I believe many of these authors wrote episodes.

Masters: It's kind of shocking just to think that "Star Trek" was imperiled at any point because today it is an institution.

Alexander: Yeah.

It was doing something so radically different, sort of maturing science fiction television as the genre in print was maturing, as well.

Masters: Is there something fundamentally different about science fiction as a literary or television genre, even, that inspires this sort of impassioned fandom?

Alexander: It's a great question.

I think science fiction can help introduce quite complex and large-scale questions to audiences, and what science fiction does better than other genres is that it sort of invites you in to participate, and I think people love that.

I think people respond to that.

♪ Masters: In the 1930s, sci-fi authors and fans in Los Angeles found a home in the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, better known as LASFS.

It was more than just a place to geek out about the latest pulp magazine.

Under pseudonyms, writers tackled big issues and taboo topics, limited only by their imaginations, and nearly a century later, they're still going strong.

One of its founding members, Forrest Ackerman, had a soft spot for the House of Pies... Woman: I think I'll have that fresh peach pie.

Masters: Do you have blueberry pie?

so naturally, I headed there to chat with some current LASFS members and dig into a slice.

So you're all members, longtime members, of this storied club.

Man: Mm-hmm.

Masters: You've probably met and spoken with and chatted sci-fi with some pretty big names.

Man: Oh, yeah.

Different man: Yeah.

Warren: Robert A. Heinlein came to the club several times.

Man: I like to say that Mr.

Heinlein didn't like me, but Isaac did, Isaac Asimov.

I've met a lot of writers.

Some of them to this day are good friends.

Man: The author interaction was actually why and how I joined because a friend of mine who was already a member of the club told me that two of my favorite authors were coming to the club just to hang out on a Friday evening, and I came there and had spent a delightful evening with other fans and with two of my favorite authors, and it's like, "Sure, I'll join.

Masters: And this sort of dynamic goes back to the club's origins.

Man: 1934... Masters: In '34?

Man: the overarching nationwide club was proposed, the Science Fiction League, with the idea that each town would have its own chapter, and Los Angeles became Chapter 4 of the Science Fiction League.

Masters: Wasn't number one?

Jackson: No, wasn't number one.

Masters: OK.

Jackson: We had Forrest J. Ackerman.

We had Bradbury.

We had Ray Harryhausen.

There was a core for the L.A.

group to build around, but the L.A.

stayed, decided to reinvent itself as the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

It was a convivial spot for fans to congregate, and so fans would come from other parts of the country and decide to stay here.

Masters: It didn't just survive, right?

It thrived, and it became a hugely influential group.

Jackson: Yeah.

It went through cycles.

The late fifties was kind of lean for the club.

"The Lord of the Rings" helped boost the club.

"Star Trek" helped boost the club, but the club was thriving pretty well by the mid sixties.

Masters: So for a while, you had your own clubhouse, but, I mean, I've read that famously, the group met in Clifton's downtown.

Jackson: Clifton's Cafeteria.

Masters: Right, which seems like a perfect place for a science fiction group to meet.

Smith: Well, for especially younger fans coming to something like a club, this was heaven... Masters: Ha ha ha!

Right.

Smith: so you got this sort of core group of people who were hanging out and bouncing ideas off of each other while they were eating at Clifton's.

Masters: What are some of the tendencies in science fiction produced in L.A.

versus elsewhere?

Tepper: Well, Robert, A. Heinlein's story "And He Built a Crooked House" very specifically is set in Los Angeles.

I think the first sentence is, "Americans are considered crazy anywhere in the world," and then he zeroes in on a particular block of Laurel Canyon Boulevard.

Masters: Ha ha ha!

Smith: So that's one of the things that you have as far as the ones who lived in Los Angeles were influenced by Los Angeles rather than forcing their stories to be set in Los Angeles.

Tepper: There are even some L.A.

landmarks that turn up in a number of-- a number of science fiction stories, especially filmed ones.

The Bradbury Building... Warren: Over and over.

Tepper: is in the original "Blade Runner."

It's in at least a couple episodes of "The Outer Limits."

City Hall gets demolished in George Pal's "War of the Worlds."

Jackson: And plays the "Daily Planet" building in the "Superman" TV series.

Tepper: Yes.

Yes.

It did.

Smith: Yeah, so Downtown Los Angeles as a site for visual stories is a very strong influence.

Masters: But we're here today at House of Pies because of its association with another famous LASFS member.

Warren: Forrest J. Ackerman.

Smith: Forry Ackerman was a literary agent first and foremost professionally.

We would meet either at his home, which is where his office was, or here at House of Pies, and we would have business meetings.

Warren: I was great friends with Forrest J. Ackerman.

My husband and I spent a lot of time at his old place on Sherwood Drive, and-- Masters: Was that the Ackermansion?

Warren: Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Masters: OK.

Yeah.

Warren: He's the one who recommended that we go to LASFS, and we loved it, just fit right in.

Smith: He was the single person who connected the most aspects of the science fiction community into one person.

Warren: Yeah.

He was a very important bridge between the older science fiction writers and fans and the young ones because the young people liked his magazine "Famous Monsters of Filmland," and he introduced them to fandom and to the conventions.

He would have parties at his house where he'd invite all the old authors, all of them.

He was a very important person to bring all of that together.

Masters: Ackerman certainly had alter egos, other identities.

It seems like one of the benefits of getting into sci-fi but, you know, joining a club like this, writing science fiction, could be to explore different identities, right?

Tepper: Science fiction writers, of course, have, for the large part, not been afraid to experiment with story styles.

Characters who change their genders have been part of science fiction over the years... Masters: Mm.

Tepper: or characters who are in societies where gender is either all-important or superfluous... Masters: Yeah.

Tepper: or always changing.

Warren: "Left Hand of Darkness."

Tepper: Yes.

"Left Hand of Darkness," by Ursula K. LeGuin, is an example of that there.

Masters: We're talking about decades ago, science fiction was experimenting with this, and-- Warren: Well, homosexuality as a movement, a lot of it started in LASFS, in Science Fiction Club.

Jimmy Kepner was an important member of LASFS.

Masters: James Kepner, uh-huh.

Warren: Yes.

He was part of the movement in Los Angeles, and it started with LASFS.

Jackson: You come into LASFS out of the cold, cruel world, you have the opportunity to say, "This is who I am."

Warren: The most important thing was not being understood, but being accepted and tolerated... Masters: Yeah.

Warren: as you are.

You come in, and you're yourself, and you're accepted.

♪ Masters: LASFS provided a safe space where progressive, even subversive, ideas circulated and where countercultural voices spoke freely.

One of those voices belonged to Jim Kepner, both an avid sci-fi fan and a pioneering gay rights advocate.

His personal collection later became the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, an archive so massive, it now fills an entire former frat house.

It was here, through some scholarly sleuthing, that the deep ties between sci-fi fandom and early gay rights activism came to light.

♪ So, Joseph, nearly 15 years ago now, you were going through a lot of these materials here at the ONE Archives, and a story emerged.

Joseph: In the very beginning, I was looking at "Uranian Worlds," which was a bibliography by Eric Garber, and that told me that there were a lot of people in science fiction who were queer, and I didn't even know that that existed.

In this particular context, you have people going to occult gatherings, to science fiction gatherings, and they allowed them in because they're already outsider spaces.

Woman: These are some of the membership cards, including the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

Masters: I see Tiggrina.

Woman: Tigrina.

Masters: Yeah, Tigrina.

Right.

Woman: Yep.

Masters: Weird Tales Club, Fourth World Science Fiction Convention Society.

Woman: Right, so not only do they have local meetings, but then they have these conventions, and everyone meets up across the nation.

It really does look at this early moment of science fiction fandoms and communities as a place where what we would now call queer individuals really thrived and found each other and started early queer organizing, especially Lisa Ben, who writes the first-ever kind of lesbian 'zine called "Vice Versa," and Jim Kepner, who are heavily involved in science fiction fandom and LASFS.

Lisa Ben, she writes in Voice of Imagi-Nation, which is Ackerman's publication, that she wants to get away from the straight and narrow path, getting away from a really strict and religious family and a family that was difficult in a lot of ways, and so science fiction fandom and that community becomes a space where she can really thrive and be herself, and we're using Lisa Ben as her name, but that's really her later adopted acronym.

That's an anagram for "lesbian," but during this time, she goes by Tigrina The Devil Doll, and you'll see in some of her materials.

Masters: People are trying to escape religious constrictions.

Boy, she really embraced that... Hawkins: Yes.

Yes.

Masters: so why were these science fiction clubs such a fruitful place for exploring different social realities or inhabiting different identities?

Johnson: Well, I think science fiction fandom and science fiction communities were really great for exploring things that didn't exist in reality right now but could exist in the future.

This moment in society, kind of queerness isn't accepted.

We're talking about the 1950s, the Lavender Scare, McCarthyism.

You can get fired for being gay and working in the public service, but there's an idea that, you know, this might not always be the reality that we're living in.

Masters: So you have rockets going into space, it feels like you're living in the material future, so why not imagine a social future close at hand?

Johnson: Exactly.

Hawkins: The other really important thing to think about is that they control this space.

There are these young people who are thinking independently and wanting to be in a space that is all their own.

They become spaces that are underground, that are accessible to them, that they control, and that they fashion into what they want them to be.

Johnson: In addition to publishing not just the fanzines that talk about maybe a review of a recent book or magazine or a film, they also realize how dense of a community this is, and so Ackerman also publishes-- maybe we can look at this item right here--he publishes one iteration of the "Fancyclopedia."

Masters: "Fancyclopedia."

Johnson: It details different terms to give folks a kind of encyclopedic view of the fan community at the time.

Hawkins: So these kinds of abbreviated things are when you're reading in their magazines, they're occulted so that it's really hard for you to understand what they are unless you're boned up on the information.

Johnson: Which is part of the control... Hawkins: Right.

Johnson: because if you're in the know and in the group, then you know what you're talking about, and for those outside, they don't, so it de facto becomes a kind of safer space.

This is "LASFS Album" from 1966, published on the anniversary of their 1,500th meeting... Masters: Wow.

Johnson: and so it's kind of like a yearbook of sorts, and so this is 1938-39, which includes Tigrina, Ray Bradbury, Elmer Perdue, and this is Forrest Ackerman and Myrtle Douglas at the World Science Fiction Convention, 1939... Masters: In costume.

Johnson: which is what we think is the first cosplay ever, so this just kind of birthed the whole idea of cosplay.

Masters: Amazing.

So was there something about L.A.

that really encouraged this imaginative thinking?

Hawkins: I think that it was on the frontier.

The East Coast of the United States was at this point still mired in class hierarchy.

Los Angeles was the new frontier.

They're making a world of their own fashion.

They want to be in a world that they've created, and this is part of their doing that.

Masters: So a lot of this material is produced during the 1930s and during World War II.

What happens after the war?

Hawkins: Well, a lot of things happen.

First wave of feminism occurs.

Civil rights issues become really predominant.

I think the emphasis is less on having these club groups where they get together and they produce science fiction to a professional industry of what is science fiction beyond that.

Masters: Ah, so it's DIY.

Yeah.

Hawkins: Yes.

This is all DIY, and it's people making it for themselves where later it becomes corporations that own, publishing companies that are producing.

You have a lot of folks moving into the professional sphere that couldn't do it during the war.

Masters: And there are probably different themes that emerge, too, as the broader culture changes.

Johnson: Science fiction, like any other publishing, reflects its time, so as we were just seeing a lot during the war is very much about what's going to happen with the atomic bomb, what's going to happen during the Cold War, what's going to happen with new rockets, and so as these different social movements become more present, science fiction reflects that, as well.

Masters: As the years passed, science fiction moved from niche to mainstream, but it never lost its edge.

One Southern Californian who pushed the boundaries of the genre was Pasadena's own Octavia Butler.

Her work, deeply rooted in her experience and her community, tackled issues of gender, race, and class while keeping one foot firmly in the world of sci-fi.

I met up with Butler expert Ayana Jamieson at one of the author's favorite spots-- Vroman's, a Pasadena institution and one of Southern California's oldest bookstores.

So L.A., or Greater Los Angeles, has these really strong associations with science fiction.

Where does Octavia Butler fit in?

Jamieson: I think she was very well-versed in knowing ways that people have been left out or deficiencies in the narratives that were told already.

She loved the genre because, she said, it had no closed doors, but also she didn't like the way that people were portrayed, in particular women and marginalized people, so in that way, she really sets herself apart.

She says she's writing different ways of being human, as opposed to universalizing everything.

Masters: So you've probably read more words written by Octavia Butler than anybody.

We're talking about published works, of course, but her archives, her personal papers, anything you could get your hands on, right?

Jamieson: And interviews and other video recordings.

I mean, someone else can say that they have, but in her archives, there are, you know, many, many, many letters, grocery lists, drafts of things that are not published, and I've really gotten into a lot of those, and I think they tell us a lot more about her association with L.A.

and Pasadena and California and how geography is really embedded, kind of, in our sense of self, and that sense of place never leaves her work.

Masters: Yeah.

If you read a book like, right over here, "Parable of the Sower," I mean, Southern California is all over this book.

Robledo is a suburb of Los Angeles, and they actually walk the highways.

Masters: [Indistinct] Jamieson: Yes.

We see the San Gabriel Mountains.

We see the grapevine and fires, and we see suburbs and sprawl and pollution, but it's very specifically Californian, and then in "Mind of My Mind," the book that comes in this series chronologically, she has her main characters living in the Wrigley Rose Parade house, so these are things that are in the archive where you might not see that name show up in the published work, but you'll see her notes in a photocopy saying, "This is Larkin House."

That kind of audacity when she was writing these stories in her teens,--like 12, 13, 14, 15--then publishing them as the first set of books that she published, she's really grounding herself in this reality and changing that psychological landscape for herself and also for us when we read it.

Masters: Now, when you say she's grounding herself in this reality or the reality she was living in at the time, she was also critiquing that reality, right?

Jamieson: Oh, absolutely.

Her mother was part of the First Great Migration.

Her family came from Louisiana and a sugar plantation, and her mother was a maid who had had 3 years of education, so think about being a 3-year-old or a 4-year-old who has to sit down and be quiet and is seeing her mother go in and out of back doors, so I think she really saw those power dynamics from an early age and started to unpack what that meant.

If you grew up in this area, it's not like you have to go to some other community to see that inequality.

You literally could go south, or you can go west, or you can go east, and you can see that right there.

Masters: And Pasadena was, in many ways, de facto segregated.

I mean, I think I recall that she referred to where she grew up as Jim Crow California.

Jamieson: Oh, absolutely.

It's well-known by people who live in the city that there are, like, bus routes and streets that you cannot go on.

Like Foothill Boulevard--which used to be Route 66, right-- there were places that you could not go without, like, a written pass above this line, so above this line was a sundown area, right?

She would say her mother would get, like, pulled over, or police would come and ask her what she was doing when she was changing a tire and things like that.

Masters: So a big part of the L.A.

sci-fi tradition is this community that was built up around it--I mean, the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

Did Butler have a similar community that she plugged into?

Jamieson: Well, she would attend Loscon, and she did get invited to be guest of honor, but I think things mostly took off after 1970, so once she went to the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop, she went to her first con when she was there, but she was, like, the only Black person.

She came back here, and the community that she had was sort of, like, people's grandma inviting her for a book club, right... Masters: Uh-huh.

Jamieson: So she would go to people's houses and go to their homes and, like, discuss her books and sign her books, so there was, like, this underground community that was above and beyond what was happening in the larger sci-fi fandom community.

Masters: Butler has been inducted into this pantheon of sci-fi greats.

What does that mean to a young reader today?

Jamieson: It means that they're already present.

They're not having to, like, scrounge and look for representation and figure out where they can see themselves, and they don't have to just be forced to identify with a dominant character, right?

There are so many different types of people and different types of bodies and different types of family situations and different types of genders in Butler's work that she really appeals to a wide audience in ways that other writers in the so-called canon really have not, so I think she made space not only for people in science fiction, but also many other genres.

♪ Masters: Los Angeles has shaped science fiction at nearly every stage of its evolution.

Whether as the backdrop for Octavia Butler's eerily accurate visions or as a gathering place where fans connect and dream, L.A.

remains a city where imagination thrives and the future is always an open book.

Hi.

Woman: Hi.

Find everything OK?

Masters: Yeah.

That's it.

Woman: All right.

Awesome.

Haven't read any of these.

[Beep] ♪ This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill philanthropy.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep2 | 5m 51s | Ayana Jamieson describes Butler's legacy as an author who wrote “different ways of being human." (5m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep2 | 5m 26s | Alexis Bard Johnson and Joseph Hawkins explain how Sci-Fi fandoms welcomed queer people. (5m 26s)

Preview: S8 Ep2 | 30s | Uncover the origins of the sci-fi genre and its unique connection to historic Los Angeles. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal