Sci-Fi Fandom

Clip: Season 8 Episode 2 | 5m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

Alexis Bard Johnson and Joseph Hawkins explain how Sci-Fi fandoms welcomed queer people.

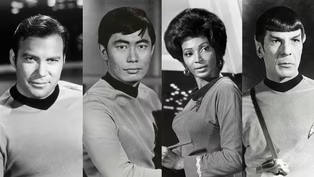

In the mid 1900s the future felt imminent amid ideas of potential space travel. This led many people to begin to imagine what a social future could look like. Using Science Fiction as a vessel, many local meetings and larger conventions already on the “fringes of society” welcomed queer people into their imaginations of the future. These fandoms became thriving examples of early queer organizing.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Sci-Fi Fandom

Clip: Season 8 Episode 2 | 5m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

In the mid 1900s the future felt imminent amid ideas of potential space travel. This led many people to begin to imagine what a social future could look like. Using Science Fiction as a vessel, many local meetings and larger conventions already on the “fringes of society” welcomed queer people into their imaginations of the future. These fandoms became thriving examples of early queer organizing.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Lost LA

Lost LA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSo, Joseph, nearly 15 years ago now, you were going through a lot of these materials here at the ONE Archives, and a story emerged.

Joseph: In the very beginning, I was looking at "Uranian Worlds," which was a bibliography by Eric Garber, and that told me that there were a lot of people in science fiction who were queer, and I didn't even know that that existed.

In this particular context, you have people going to occult gatherings, to science fiction gatherings, and they allowed them in because they're already outsider spaces.

Woman: These are some of the membership cards, including the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

Masters: I see Tiggrina.

Woman: Tigrina.

Masters: Yeah, Tigrina.

Right.

Woman: Yep.

Masters: Weird Tales Club, Fourth World Science Fiction Convention Society.

Woman: Right, so not only do they have local meetings, but then they have these conventions, and everyone meets up across the nation.

It really does look at this early moment of science fiction fandoms and communities as a place where what we would now call queer individuals really thrived and found each other and started early queer organizing, especially Lisa Ben, who writes the first-ever kind of lesbian 'zine called "Vice Versa," and Jim Kepner, who are heavily involved in science fiction fandom and LASFS.

Lisa Ben, she writes in Voice of Imagi-Nation, which is Ackerman's publication, that she wants to get away from the straight and narrow path, getting away from a really strict and religious family and a family that was difficult in a lot of ways, and so science fiction fandom and that community becomes a space where she can really thrive and be herself, and we're using Lisa Ben as her name, but that's really her later adopted acronym.

That's an anagram for "lesbian," but during this time, she goes by Tigrina The Devil Doll, and you'll see in some of her materials.

Masters: People are trying to escape religious constrictions.

Boy, she really embraced that... Hawkins: Yes.

Yes.

Masters: so why were these science fiction clubs such a fruitful place for exploring different social realities or inhabiting different identities?

Johnson: Well, I think science fiction fandom and science fiction communities were really great for exploring things that didn't exist in reality right now but could exist in the future.

This moment in society, kind of queerness isn't accepted.

We're talking about the 1950s, the Lavender Scare, McCarthyism.

You can get fired for being gay and working in the public service, but there's an idea that, you know, this might not always be the reality that we're living in.

Masters: So you have rockets going into space, it feels like you're living in the material future, so why not imagine a social future close at hand?

Johnson: Exactly.

Hawkins: The other really important thing to think about is that they control this space.

There are these young people who are thinking independently and wanting to be in a space that is all their own.

They become spaces that are underground, that are accessible to them, that they control, and that they fashion into what they want them to be.

Johnson: In addition to publishing not just the fanzines that talk about maybe a review of a recent book or magazine or a film, they also realize how dense of a community this is, and so Ackerman also publishes-- maybe we can look at this item right here--he publishes one iteration of the "Fancyclopedia."

Masters: "Fancyclopedia."

Johnson: It details different terms to give folks a kind of encyclopedic view of the fan community at the time.

Hawkins: So these kinds of abbreviated things are when you're reading in their magazines, they're occulted so that it's really hard for you to understand what they are unless you're boned up on the information.

Johnson: Which is part of the control... Hawkins: Right.

Johnson: because if you're in the know and in the group, then you know what you're talking about, and for those outside, they don't, so it de facto becomes a kind of safer space.

This is "LASFS Album" from 1966, published on the anniversary of their 1,500th meeting... Masters: Wow.

Johnson: and so it's kind of like a yearbook of sorts, and so this is 1938-39, which includes Tigrina, Ray Bradbury, Elmer Perdue, and this is Forrest Ackerman and Myrtle Douglas at the World Science Fiction Convention, 1939... Masters: In costume.

Johnson: which is what we think is the first cosplay ever, so this just kind of birthed the whole idea of cosplay.

Masters: Amazing.

So was there something about L.A.

that really encouraged this imaginative thinking?

Hawkins: I think that it was on the frontier.

The East Coast of the United States was at this point still mired in class hierarchy.

Los Angeles was the new frontier.

They're making a world of their own fashion.

They want to be in a world that they've created, and this is part of their doing that.

Masters: So a lot of this material is produced during the 1930s and during World War II.

What happens after the war?

Hawkins: Well, a lot of things happen.

First wave of feminism occurs.

Civil rights issues become really predominant.

I think the emphasis is less on having these club groups where they get together and they produce science fiction to a professional industry of what is science fiction beyond that.

Masters: Ah, so it's DIY.

Yeah.

Hawkins: Yes.

This is all DIY, and it's people making it for themselves where later it becomes corporations that own, publishing companies that are producing.

You have a lot of folks moving into the professional sphere that couldn't do it during the war.

Masters: And there are probably different themes that emerge, too, as the broader culture changes.

Johnson: Science fiction, like any other publishing, reflects its time, so as we were just seeing a lot during the war is very much about what's going to happen with the atomic bomb, what's going to happen during the Cold War, what's going to happen with new rockets, and so as these different social movements become more present, science fiction reflects that, as well.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep2 | 5m 51s | Ayana Jamieson describes Butler's legacy as an author who wrote “different ways of being human." (5m 51s)

Preview: S8 Ep2 | 30s | Uncover the origins of the sci-fi genre and its unique connection to historic Los Angeles. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal